Germany’s housing and heating sector has become a centrepiece of its evolving climate and social policy agenda. Persistent housing shortages in metropolitan regions have driven rents to historically high levels in many cities, placing increased pressure on low- and middle-income households. At the same time, sharply higher construction and borrowing costs have weighed heavily on the sector. Capacity bottlenecks in the building industry, combined with complex planning and permitting procedures, have further slowed down new construction and renovations, even as demand continues to rise. These challenges are compounded by a long-standing backlog in energy renovation across an ageing building stock, in which many residential and commercial properties still rely on inefficient envelopes and fossil-fuel heating systems.

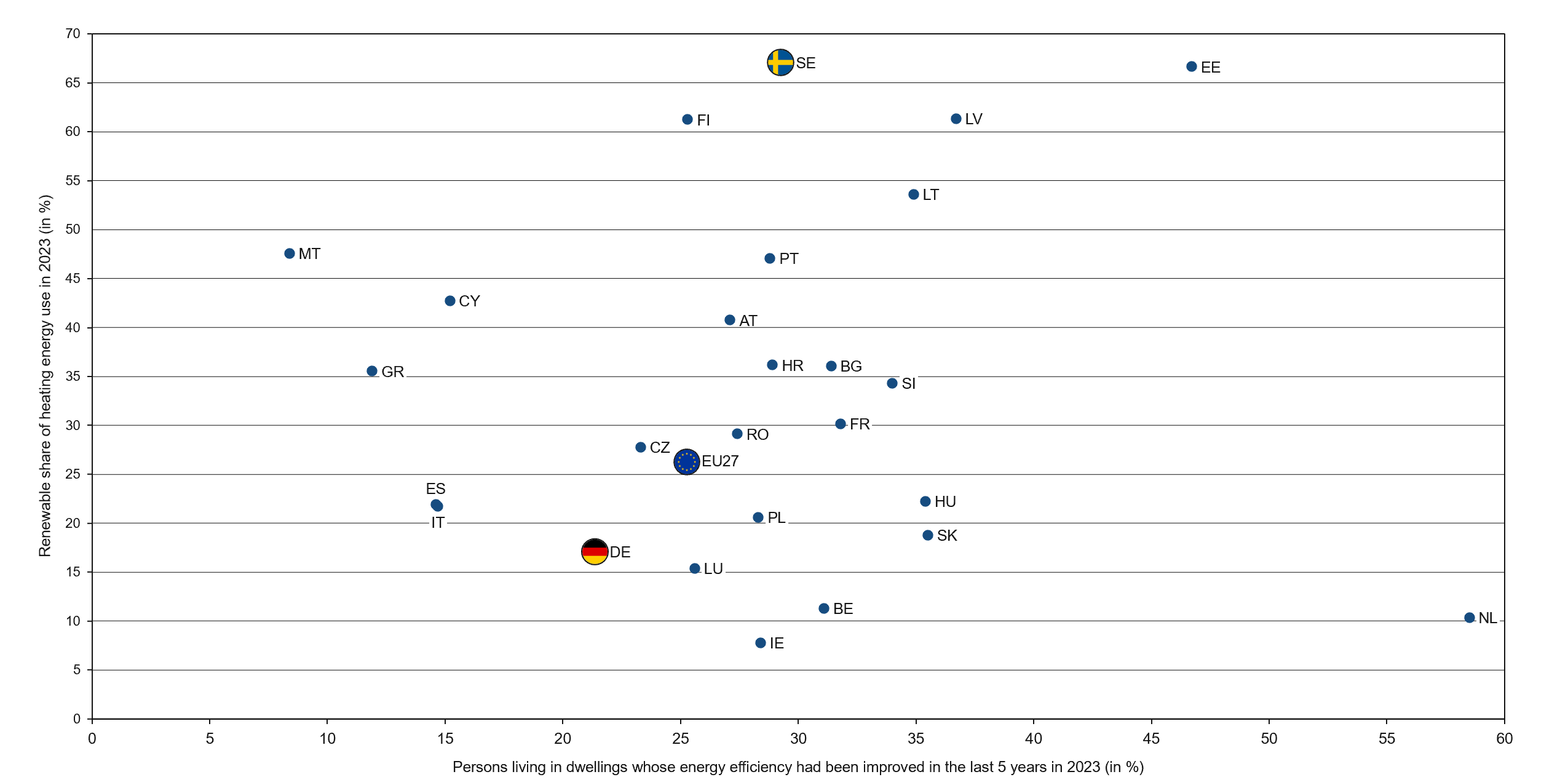

In quantitative terms, the building sector accounts for around 35% of Germany’s final energy consumption and roughly 30% of energy-related CO₂ emissions. Within private households, around 70% of final energy use is attributable to space and water heating, while in commercial buildings the share is about 50%. Yet only around 18% of final energy consumption for heating and cooling is covered by renewable sources, a share that has remained largely stagnant in recent years. To align with national climate targets, the energy demand of buildings must be substantially reduced. In practice, this requires increasing the annual renovation rate from around 1% today to roughly 2.5% of the building stock, alongside a structural shift away from oil and gas towards climate-friendly district heating networks and heat pumps powered by green electricity. Furthermore, only around 20% of people live in dwellings that have undergone energy-efficiency improvements in the past five years, a share that is lower than both the EU average and Sweden (Figure 1). Taken together, these factors have contributed to a widely shared perception of a “permanent crisis” in the German housing market, in which social, affordability and climate objectives are tightly intertwined and cannot be addressed in isolation.

Figure 1: Renewable share of heating energy in 2023 and share of people living in a dwelling whose energy efficiency had been improved in the last 5 years in 2023 across the EU27¹ countries

¹AT-Austria, BE-Belgium, BG-Bulgaria, CY-Cyprus, CZ-Czechia, DE-Germany, DK-Denmark, EE-Estonia, ES-Spain, FI-Finland, FR-France, GR-Greece, HR-Croatia, HU-Hungary, IE-Ireland, IT-Italy, LT-Lithuania, LU-Luxembourg, LV-Latvia, MT-Malta, NL-Netherlands, PL-Poland, PT-Portugal, RO-Romania, SE-Sweden, SI-Slovenia, SK-Slovakia.

Source: Eurostat

In response, the Federal Government is intensifying its housing initiatives across several fronts. Funding for social and affordable housing has been significantly increased, with federal co-financing to the states reaching record levels to expand and modernise the social housing stock. In parallel, subsidy schemes for climate-friendly new construction and the energy-efficient refurbishment of existing buildings are being stabilised and more closely aligned with long-term climate targets.

The heating transition is also being accelerated through amendments to the Building Energy Act and the introduction of mandatory municipal heat planning. Together, these measures are steering new investments towards heat pumps, decarbonised district heating networks, and other low-carbon heating solutions. In parallel, policymakers are also promoting serial and modular construction methods to accelerate project delivery and reduce costs in large-scale housing programmes, while pilot funding supports the conversion of underutilised commercial properties into residential use. Collectively, these initiatives are intended to transform Germany’s housing and heating sectors from largely separate policy domains into a coherent transformation pathway aligned with the country’s broader climate and social objectives.

Rebuilding Germany’s Housing Future

Germany’s building stock is large, heterogeneous and comparatively old. Of the approximately 20 million residential buildings recorded as of May 2022, more than 70% were constructed before 1990, well ahead of the introduction of today’s energy performance standards. Only about 17% of residential buildings have been built since 2000, and less than 8% since 2010. In practice, this means that a large share of homes and smaller commercial buildings still combine inefficient envelopes with conventional oil or gas heating systems. As a result, the building sector remains one of Germany’s most significant climate challenges, but also one of its most powerful levers for change.

The Federal Government’s Long-Term Renovation Strategy reflects both dimensions. On the one hand, final energy consumption for heating in buildings fell by around 13–14% between 2008 and 2018, driven by efficiency improvements and existing subsidy schemes. On the other hand, progress has been too slow to meet the objective of achieving a nearly climate-neutral building stock by 2050. The rate of energy-focused renovations has stagnated at roughly 1% of the building stock per year, around half the level required to bring heating demand in line with climate targets.

Sweden offers a useful point of comparison. Despite a similarly old building stock (around 73% were built before 1980 and only about 10% after 2000), Sweden illustrates what can be achieved when renovation efforts are consistently aligned with clean heat policies. While both countries share comparable structural legacies, it is ultimately the pace and consistency of renovation and new-build policies that will determine whether the housing stock becomes an asset for the transition or remains a constraint.

At the same time, Germany’s challenge is not only one of slow renovation, but also of insufficient new construction. An acute housing shortage persists, particularly in metropolitan regions, where complex and lengthy planning and permitting procedures can delay new projects for years. To address this bottleneck, the Federal Government has introduced the so-called Bau-Turbo, a temporary instrument under the Federal Building Code designed to fast-track new housing developments.

Effective until the end of 2030, the Bau-Turbo allows municipalities to deviate from standard planning procedures in order to accelerate housing delivery. In practice, this enables local authorities to bypass the often lengthy preparation of a full development plan and instead decide directly on individual projects. Under this regime, additional dwellings can be approved following a three-month review period, with applications deemed approved unless explicitly rejected within that timeframe. The scope is intentionally broad, covering new residential construction as well as rooftop additions, extensions, and the conversion of commercial properties into housing.

Safeguards remain in place. Deviations are permitted only where preliminary assessments show no significant environmental impacts, where they are necessary to accelerate delivery, and where local interests are adequately considered. In parallel, the Federal Government is strengthening protections in tight housing markets, such as restrictions on the conversion of rental apartments into condominiums and the extension of the rent brake, to ensure that faster construction and densification do not translate into new forms of displacement.

Taken together, these developments mark the beginning of a comprehensive reset in Germany’s housing policy. The objective is to combine a step-up in energy renovation with faster planning processes, wider use of serial and modular construction, and the activation of existing buildings, including conversions of commercial space into residential use, to turn its ageing building stock from a structural constraint into a central lever for creating affordable, climate-compatible housing.

Towards Renewable Heat

If the age and quality of the building stock determine how much heat is required, the design of the heating system determines how clean that heat is. Germany’s challenge is therefore twofold: to reduce demand through renovation and energy-efficient new construction, while at the same time shifting heat supply away from fossil fuels towards renewable sources.

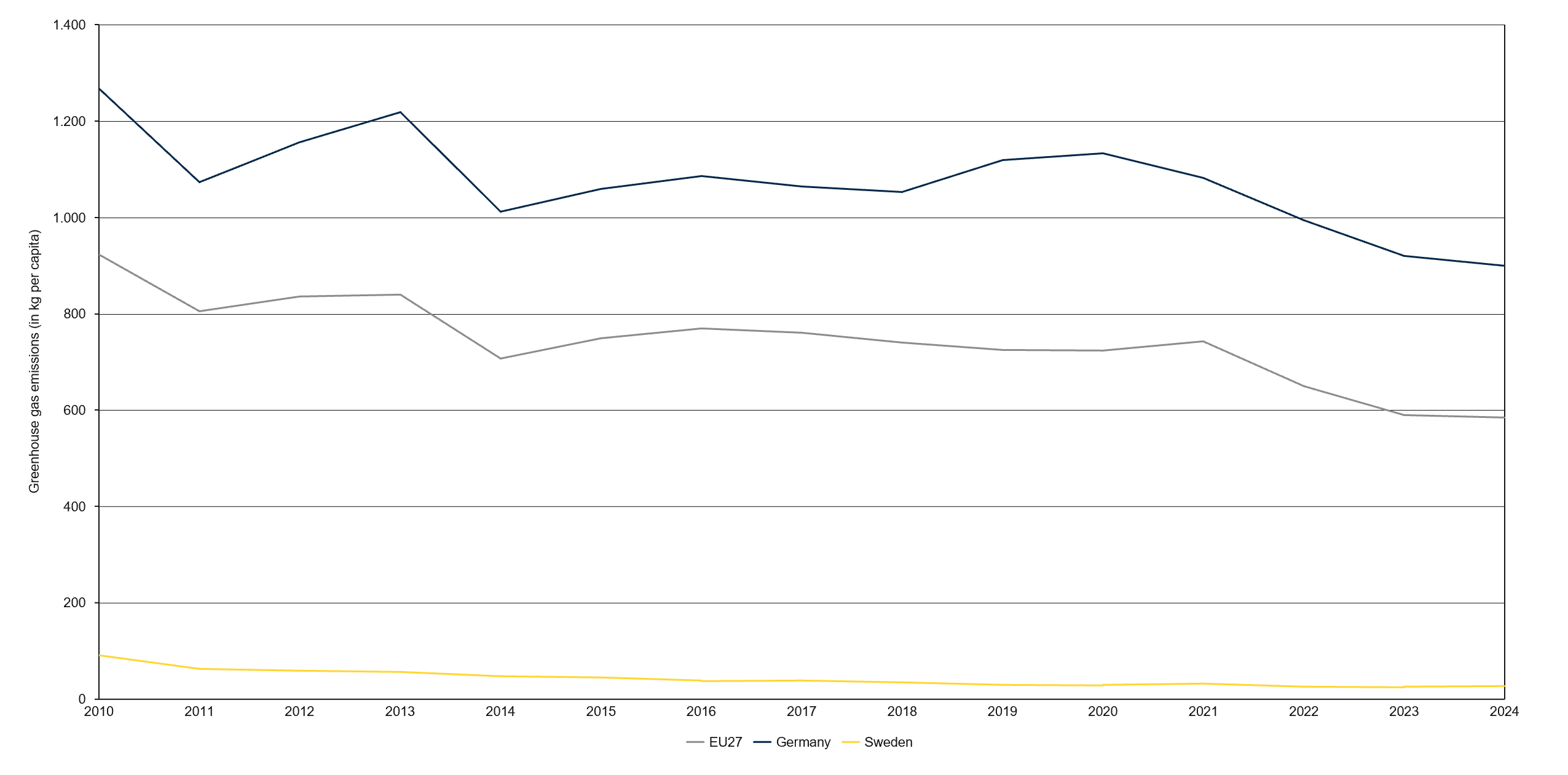

In quantitative terms, Germany is still at an early stage of this second transition. Only around 18% of final energy consumption for heating and cooling is currently covered by renewables, and this share has effectively stagnated in recent years despite rising climate ambition. By contrast, Sweden’s heating and cooling sector is already far more advanced in terms of decarbonisation. Eurostat data for 2023 show that 67.1% of Sweden’s heating and cooling demand is met by renewable energy, the highest share in the EU, driven mainly by biomass-based district heating and the widespread deployment of heat pumps. As Figure 2 illustrates, household emissions from heating and cooling in Sweden are not only on a clear downward trajectory, but also remain at a fraction of the levels observed in Germany and the EU27. Given that both countries have similarly old building stocks, the contrast is not primarily driven by physical constraints. Rather, it reflects how quickly renovation policy, heat network planning and technology deployment are aligned.

Figure 2: Greenhouse gas emissions by households for heating and cooling, from 2010 to 2024 (in kg per capita)

Figure 2: Greenhouse gas emissions by households for heating and cooling, from 2010 to 2024 (in kg per capita)

Source: Eurostat

Germany’s heating transition is now being driven by a combination of regulatory targets and planning obligations. With the revised Building Energy Act (GEG), the Federal Government has introduced the principle that new heating systems should, in future, use at least 65% renewable energy. Since 1 January 2024, this already applies to new buildings in designated development areas; in existing buildings and infill locations, the requirement is phased in and tightly linked to municipal heat planning. The logic is straightforward: homeowners should not have to guess whether a district heating connection or an individual heat pump will be the long-term solution in their street, the local heat plan should provide that visibility.

Municipal heat planning therefore constitutes the second pillar of the heat transition. Large cities are required to complete their plans by mid-2026, with all other municipalities by mid-2028. These plans are expected to identify zones for expanding or decarbonising district heating networks, areas where individual or central heat pumps are expected to dominate, and locations where other solutions (such as climate-neutral gas or hybrid systems) are likely to play a complementary role. In practical terms, this means that new fossil-only boilers will gradually be phased out of the market, and replacement decisions will increasingly be guided by whether a building is located in a future network area or not.

Alongside regulation and planning, the federal energy research strategy sets “sprinter targets” for the accelerated development of key technologies. By 2030, high-temperature heat pumps are expected to supply process heat at temperatures above 300°C in industrial applications. Geothermal energy is to contribute a substantially larger share to the overall heat mix, while new generations of insulation materials and thermal storage technologies are intended to reduce primary energy requirements and make renewable heat solutions more flexible and competitive. Taken together, these research and innovation priorities are designed to ensure that, as the building stock becomes more energy efficient, a robust pipeline of mature technologies is available to meet the remaining heat demand with minimal emissions.

In summary, Germany’s housing policy reset and its heating transition are two sides of the same coin. Deep renovation and more efficient new housing bring down demand, while the GEG, municipal heat planning and targeted innovation policy are shifting heat supply towards heat pumps, renewable district heating and other low-carbon solutions. Sweden’s experience illustrates how binding municipal heat planning can accelerate the heating transition. For decades, Swedish municipalities have coordinated land-use planning, district heating expansion and local energy strategies, providing utilities and building owners with early clarity on long-term heating pathways. This sequencing has reduced investment risk and enabled the large-scale deployment of renewable district heating and heat pumps. Germany’s current approach points in the same direction, but its ultimate impact will depend on how quickly local heat plans are translated into clear and credible investment signals.

Investment Outlook

On the investment side, the Special Fund for Infrastructure and Climate Neutrality (SVIK) establishes a clear multi-year funding corridor for housing. Federal housing investments are planned to increase from EUR 0.3 billion in 2025 to EUR 1.2 billion by 2029 (Table 1). This is complemented in 2025 by funds specifically earmarked for housing infrastructure, climate-friendly construction, ownership support for families and other schemes, climate-friendly newbuilds in the low-price segment, and conversions from commercial properties to residential use.

|

Planned spending |

2025 |

2026 |

2027 |

2028 |

2029 |

|

|

- in EUR billion - |

||||

|

Housing investments (SVIK) |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.7 |

1 |

1.2 |

Table 1: Key figures for federal housing investments planned as part of SVIK

Source: Federal Ministry of Finance

In parallel, further programme funds from the Climate and Transformation Fund (KTF) are being channelled into schemes supporting climate-friendly newbuilds, the activation of the construction backlog, and refurbishment and conversion of existing buildings. Taken together, these funding streams signal that Germany’s housing and heating transition is backed by an expanding and dedicated public funding base rather than relying on short-term one-off measures.

Opportunities for Swedish companies

Germany’s housing and heating reset creates a sizeable, long-term market for solutions that Sweden already applies at scale, including efficient renovation, climate-smart new construction, and clean heat technologies. With an ageing building stock, a renovation rate that needs to at least double, and growing federal funding streams through SVIK, the KTF and the core budget, demand is set to increasingly shift from isolated pilot projects towards repeatable, industrialised solutions. For Swedish companies, several opportunity fields are particularly relevant:

|

|

Opportunity |

|

Energy renovation and serial solutions |

Industrialised, prefabricated façade/roof systems, combined with integrated HVAC units, can help raise Germany’s renovation rate in standardised multi-family buildings. |

|

Climate-friendly social and affordable housing |

Nordic experience with multi-storey timber, low-energy designs and lifecycle thinking supports cost-efficient, climate-aligned social and cooperative housing. |

|

Conversion of commercial buildings to housing |

Architectural and engineering know-how in adaptive reuse is increasingly valuable for projects as Bau-Turbo and new programmes make conversions more attractive. |

|

District heating, heat pumps and system integration |

Swedish utilities and technology suppliers offer proven solutions for the decarbonisation and optimisation of district heating networks and large-scale heat pump systems. |

|

Digital planning and portfolio optimisation |

BIM-based tools and data-driven portfolio strategies can help German cities and housing companies prioritise renovations and align projects with climate and funding targets. |

Table 2: Key beneficiaries of SVIK

Source: Business Sweden

Sources:

- Bundestag (2025), Haushaltsausschuss billigt Eckwerte für den Bundeshaushalt 2025, retrieved on 27/11/2025 from https://www.bundestag.de/presse/hib/kurzmeldungen-1006396

- Eurostat (2025), Housing and heating costs in the EU, retrieved on 12/12/2025 from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20250305-1

- Eurostat (2024), Housing in Europe – 2024 edition, retrieved on 27/11/2025 from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/interactive-publications/housing-2024

- Federal Government (2023), Für mehr klimafreundliche Heizungen, retrieved on 12/12/2025 from https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/aktuelles/neues-gebaeudeenergiegesetz-2184942

- Federal Government (2025), Wohnungsbau-Turbo, retrieved on 12/12/2025 from https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/aktuelles/wohnungsbau-turbo-2354894

- Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (2020), Langfristige Renovierungsstrategie der Bundesregierung, retrieved on 12/12/2025 from https://www.bundeswirtschaftsministerium.de/Redaktion/DE/Publikationen/Energie/langfristige-renovierungsstrategie-der-bundesregierung.pdf

- Federal Ministry of Finance (2025), 2. Entwurf des Bundeshaushalts 2025 und Eckwerte bis 2029, retrieved on 27/11/2025 from https://www.bundesfinanzministerium.de/Content/DE/Pressemitteilungen/Finanzpolitik/2025/06/2025-06-24-2-entwurf-bhh-2025-eckwerte-bis-2029.html

- Federal Ministry of Finance (2025), Bundeshaushalt: In die Zukunft investieren, retrieved on 26/11/2025 from https://www.bundeshaushalt.de/DE/Schwerpunktthema/schwerpunktthema.html

- Federal Ministry for Housing, Urban Development and Building (2025), Haushalt des Bundesbauministeriums wächst weiter, retreived on 27/11/2025 from, from

https://www.bmwsb.bund.de/SharedDocs/pressemitteilungen/DE/2025/11/haushalt.html

- Federal Ministry for Housing, Urban Development and Building (2022), 18 Monate BMWSB: Wohnen, retrieved on 27/11/2025 from https://www.bmwsb.bund.de/SharedDocs/topthemen/DE/18-monate-bmwsb/wohnen-artikel.html

- German Environment Agency (2025), Energiesparende Gebäude – Gebäude wichtig für den Klimaschutz, retrieved on 12/12/2025 from https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/themen/klima-energie/energiesparen/energiesparende-gebaeude#gebaude-wichtig-fur-den-klimaschutz

- German Environment Agency (2025), Energieverbrauch für fossile und erneuerbare Wärme, retrieved on 12/12/2025 from https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/daten/energie/energieverbrauch-fuer-fossile-erneuerbare-waerme

- German Environment Agency (2025), Energieverbrauch nach Energieträgern und Sektoren – Allgemeine Entwicklung und Einflussfaktoren, retrieved on 12/12/2025 from https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/daten/energie/energieverbrauch-nach-energietraegern-sektoren#allgemeine-entwicklung-und-einflussfaktoren

- Statistics Sweden (SCB) (2020), Housing by age and locality type, retrieved on 12/12/2025 from https://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/en/ssd/START__MI__MI0810__MI0810B/BostAlderTatortRegN/table/tableViewLayout1/