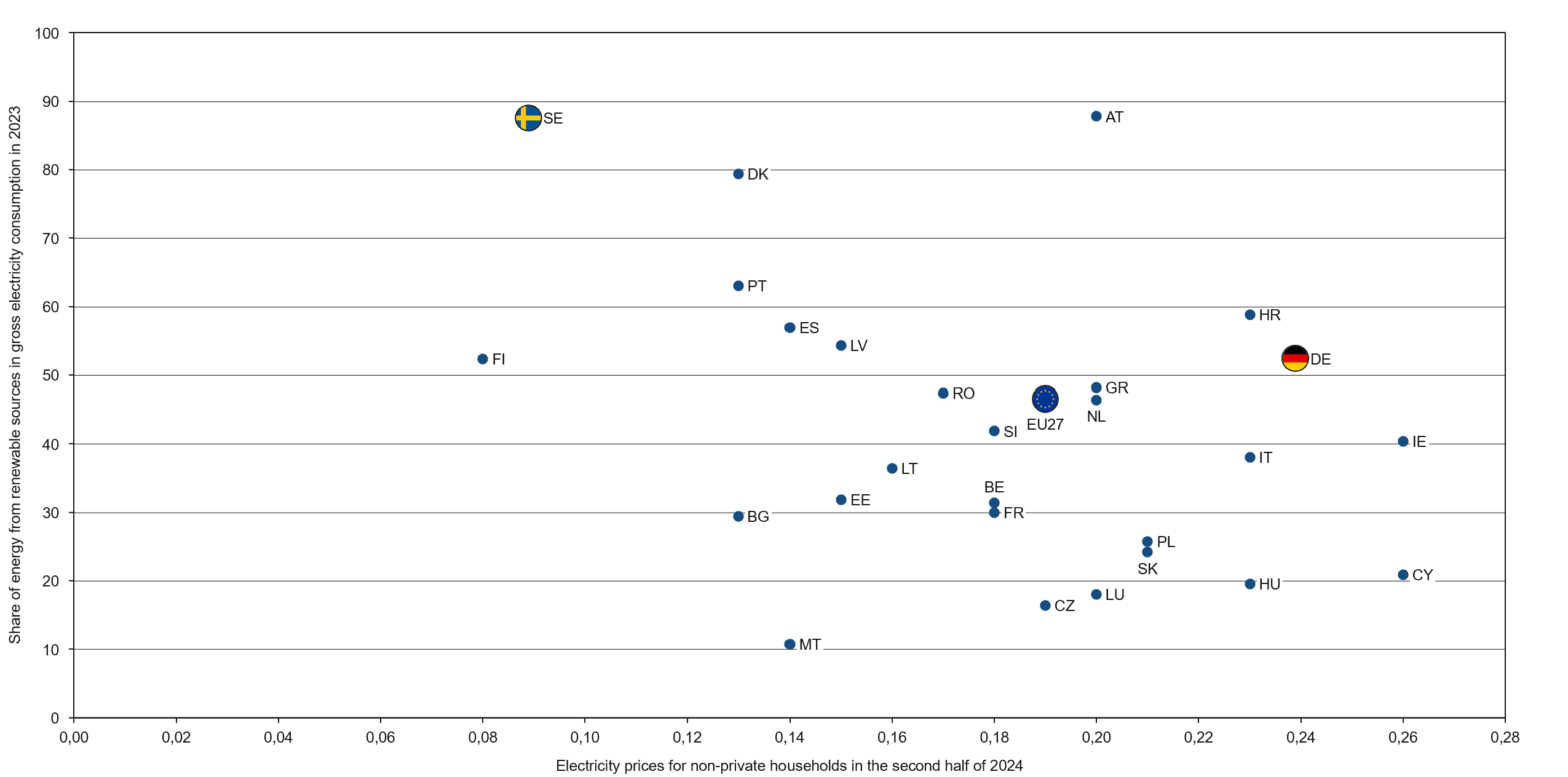

For decades, Germany has been a frontrunner in the transition to renewable energy. However, following the combined shocks of the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the country now faces a more challenging starting point. Energy prices for industry remain among the highest in Europe (Figure 1), while implementation of the energy transition continues to lag behind stated ambition in several sectors.

Figure 1: Comparison of electricity prices for non-private households in the second half of 2024 and the share of energy from renewable sources in gross electricity consumption in 2023 (no EU data for 2024 yet) across the EU27¹ countries

¹AT-Austria, BE-Belgium, BG-Bulgaria, CY-Cyprus, CZ-Czechia, DE-Germany, DK-Denmark, EE-Estonia, ES-Spain, FI-Finland, FR-France, GR-Greece, HR-Croatia, HU-Hungary, IE-Ireland, IT-Italy, LT-Lithuania, LU-Luxembourg, LV-Latvia, MT-Malta, NL-Netherlands, PL-Poland, PT-Portugal, RO-Romania, SE-Sweden, SI-Slovenia, SK-Slovakia.

Source: Federal Statistical Office

Amid these challenging conditions, structural decarbonisation is gaining momentum. In 2024, renewables accounted for around 60% of net electricity generation, representing an increase of approximately 10 percentage points compared with 2023, driven by record additions of solar PV and a continued decline in coal-fired plants. Primary electricity consumption and electricity-related CO₂ emissions are now roughly one third below 1990 levels, supported by efficiency gains, industry transformation and the coal phase-out. Simultaneously, the rollout of electric vehicle infrastructure is accelerating, supported by the target of installing one million charging points by 2030. To support these measures, significant efforts are underway to expand the electricity grid, which continues to be a major bottleneck.

At the same time, electricity prices remain a challenge, particularly for energy-intensive industries. However, pressure has eased compared with the peak of the energy crisis, and reforms to grid charges, targeted relief for key sectors and the rapid expansion of renewables are designed to gradually reduce electricity costs. In addition, the planned industrial electricity price will enable eligible companies across around 90 energy-intensive sectors to cap part of their electricity consumption at around EUR 0.05/kWh from 2026 onwards, financed through a time-limited subsidy of approximately EUR 3.1 billion and linked to mandatory investments in efficiency and clean electricity. In policy terms, this signals that the objective is not only climate neutrality, but also the explicit reduction of electricity prices over the medium term, restoring competitiveness and improving affordability for households and businesses alike.

To close the gap between ambition and reality, Germany relies heavily on targeted investment programmes and regulatory reforms. The Federal Climate Action Law enshrines the goal of climate neutrality by 2045 and a 65% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 compared with 1990 levels, covering all sectors of the economy. Financing for the transition is supported by the Special Fund for Infrastructure and Climate Neutrality (SVIK) and the Climate and Transformation Fund (KTF), which receives EUR 10 billion annually from the SVIK, as well as its share of revenues from European and national emissions trading. Taken together, these instruments indicate that Germany is not just debating the energy transition, but increasingly implementing it, with the dual objective of decarbonisation and lower, more predictable electricity prices.

Expansion of Renewable Energy and Hydrogen Infrastructure

To meet Germany’s climate neutrality target, accelerating the renewable energy deployment is a critical step, as it forms the backbone of the country’s energy infrastructure transformation. In 2023, renewables supplied around 52.3% of net public electricity generation, while total installed renewable capacity reached just over 190 GW. As a result, Germany possesses not only the world’s fourth-largest renewable power capacity, but also the largest in Europe. By contrast, Sweden’s power system is smaller in absolute terms, with around 55 GW of total installed capacity in 2023, but its electricity mix is already almost fossil-free, with roughly 90% of generation coming from renewables in 2023.

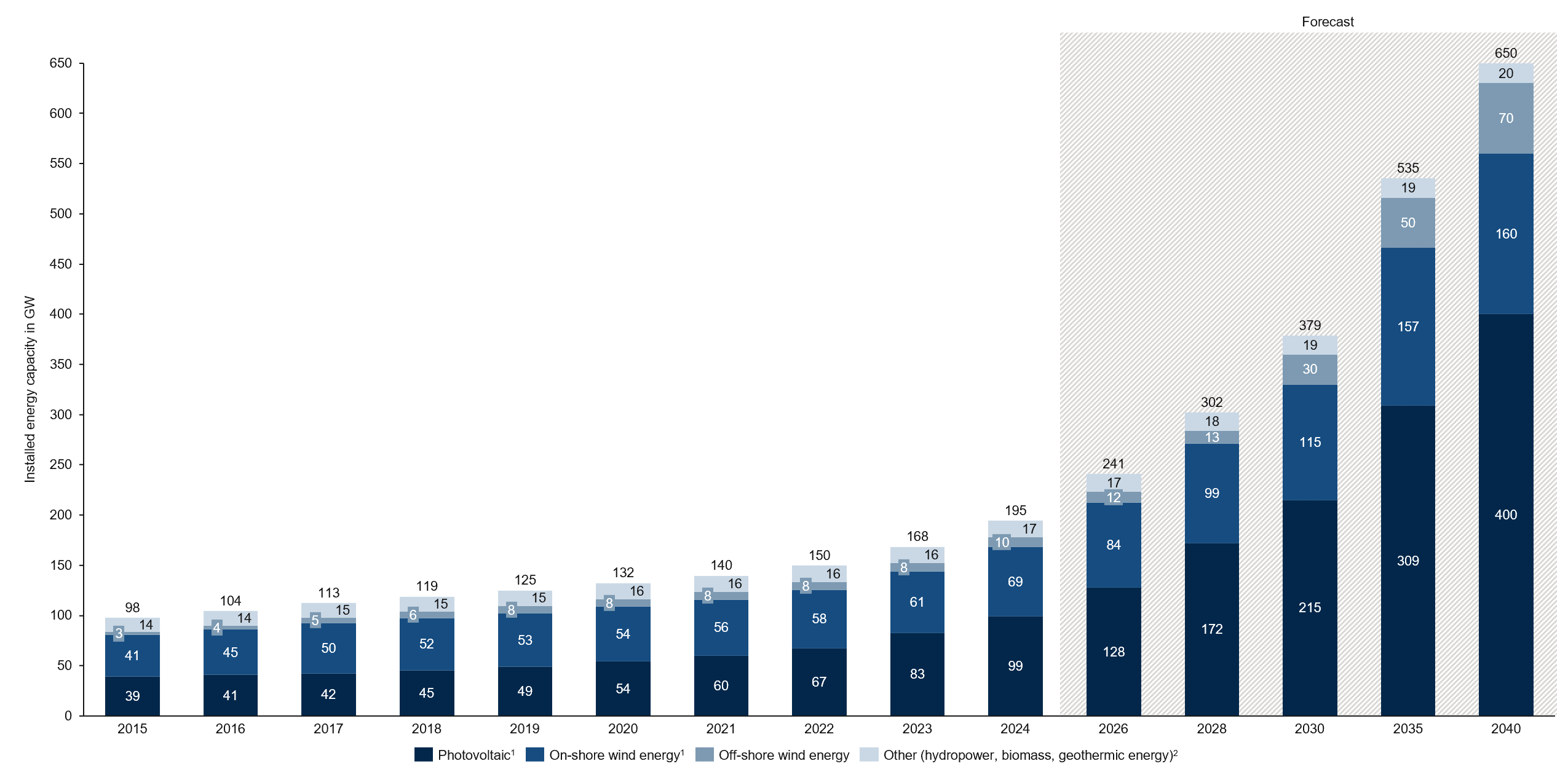

As shown in Figure 2, the expansion pathways set out in the Renewable Energies Act (EEG 2023) foresee Germany’s installed renewable capacity rising from around 190 GW in 2024 to approximately 650 GW by 2040. Most of this growth is expected to come from photovoltaics (increasing from roughly 100 GW in 2024 to around 400 GW in 2040) and onshore wind, while offshore wind scales up from a single-digit base to around 70 GW over the same period. Other renewables (hydropower, biomass and geothermal) remain comparatively stable, with growth in this category driven mainly by biomass.

Figure 2: Capacity of renewable energies in Germany from 2015 to 2040, by type (in GW)

¹According to Act on the Expansion of Renewable Energies (Renewable Energies Act – EEG 2023), Section 4 Expansion Path

²Growth driven solely by biomass, with no projections available for the other energy sources

Source: Federal Ministry of Justice, Federal Ministry of Economic Affairs and Energy, Deutsche WindGuard

Germany’s EV Charging Infrastructure Build-Out

In parallel to hydrogen infrastructure, Germany is also expanding the demand-side systems needed for electrification, most notably its EV charging network. According to the Federal Network Agency, there were 161,686 public charging points as of 1 February 2025, representing a 21% increase within one year. By 1 October 2025, this figure had risen to almost 180,000 public chargers, with a connected capacity of around 7.3 GW, giving Germany the largest total public charging capacity in Europe. As a result, Germany provides one charging point per ten electric vehicles. The Federal Government’s Masterplan Ladeinfrastruktur II and the new Charging Infrastructure Master Plan 2030 reaffirm the target of one million publicly accessible charging points by 2030, with policy emphasis now shifting from pure quantity towards reliability, ease of use and fair pricing. By contrast, Sweden provides one charging point per seven EVs and is expanding its network by about 10% annually (2023–2024). Germany’s rapid expansion of electric vehicle charging infrastructure therefore demonstrates its ambition to regain a leading position in automotive infrastructure.

Grid Constraints Remain the Central Bottleneck

Yet, all these efforts face a major challenge: the electricity grid remains a central bottleneck for Germany’s energy transition. Most new renewable capacity is located in the north and east of the country, while large industrial consumers are concentrated in the west and south. At the same time, the electrification of transport, buildings and industry is steadily increasing overall electricity demand. This makes the expansion and modernisation of the high-voltage grid one of Germany’s key infrastructure projects.

To manage this, the Federal Network Agency and the transmission system operators jointly prepare an Electricity Network Development Plan. The current plan (NEP 2037/2045) identifies needs for around 4,800 km of entirely new onshore transmission lines and approximately 2,500 km of reinforcements of existing lines, including large north–south “power highways” such as SuedLink and SuedOstLink, as well as additional connections for offshore wind in the North Sea and Baltic Sea. These projects are intended to move increasing volumes of renewable electricity reliably from generation regions to industrial centres.

In practice, grid expansion has progressed more slowly than originally planned. Approval procedures are complex, infrastructure projects often face local opposition and court challenges, and specialised construction capacity remains limited. When critical transmission lines are missing, system operators must intervene more frequently to maintain grid stability, for example by redispatching power plants or curtailing wind farms. The additional costs of these measures are reflected in network charges, which form a significant part of electricity prices for companies in Germany.

Investment Outlook

Scaling up energy infrastructure requires substantial investment. In addition to the Special Fund for Infrastructure and Climate Neutrality (SVIK), Germany relies on another major financing instrument to support its long-term energy and industrial transformation: the Climate and Transformation Fund (KTF). The KTF is the federal government’s central off-budget fund for climate action, industry decarbonisation and the energy transition. It is primarily financed through revenues from EU Emissions Trading (EU ETS) and Germany’s national carbon pricing system (BEHG). Under the current financial framework, EUR 100 billion of the SVIK’s total volume will be transferred into the KTF, equivalent to around EUR 10 billion per year. This mechanism strengthens the KTF’s capacity to fund major transformation programs.

The SVIK is designed to finance large-scale, multi-year infrastructure investments. For energy-related infrastructure, the government’s financial plan provides the following allocations:

| Planned spending | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | 2029 |

| - in EUR billion - | |||||

| Energy infrastructure (SVIK) | 0.9 | 2.1 | 2.8 | 3.2 | 3.0 |

Table 1: Key figures for energy investments planned as part of SVIK

Source: Federal Ministry of Finance

By contrast, the KTF does not publish a consolidated figure for “energy spending”, as its programmes are deliberately cross-sectoral. Measures such as hydrogen development, industrial decarbonisation, grid charge relief and building efficiency all contribute to the energy transition but are not grouped under a single budget line. As a result, only individual items within the KTF can be quantified precisely, while the total amount dedicated specifically to energy infrastructure cannot be derived directly from the fund’s budget plan.

Taken together, SVIK and KTF are not merely financial tools. They signal a long-term commitment to setting up a sustainable infrastructure, creating opportunities for businesses to align with Germany’s objectives and drive innovation.

Opportunities for Swedish Companies

Business Sweden will closely monitor developments related to Germany’s energy-related spending under the Special Fund and the Climate and Transformation Fund. These instruments are expected to trigger substantial investment in renewable energy, electricity, and hydrogen infrastructure, as well as the modernization of critical energy systems. Grid expansion, hydrogen transport networks, and “green-ready” import infrastructure will form the backbone of Germany’s future energy system, while additional opportunities will arise in areas such as storage, system integration, flexibility solutions, and industrial decarbonization. Sweden’s strong track record in clean energy, system stability, and low-carbon industrial technologies positions Swedish companies as highly relevant partners in Germany’s evolving energy transition market.

| Opportunity | |

|---|---|

| Power-to-X Solutions | Converting renewable electricity into hydrogen and other energy carriers for industrial use. |

| Area Hydrogen Technologies | Production, storage, and transport systems for hydrogen in industry and mobility applications. |

| Energy Storage | Advanced battery systems and grid-scale storage to stabilize intermittent renewable generation. |

| EV Charging Infrastructure | Smart, scalable solutions for Germany’s rapidly growing electric vehicle market. |

| Technology & System Integration | Expertise in digitalization, flexibility, and cross-border energy flows. |

Table 2: Key beneficiaries of SVIK

Source: Business Sweden

Next in the Series

In our next and final post, we will highlight how the Special Fund allocates significant resources to social housing, sustainable construction, and the heating transition.

Sources

- Deutsche WindGuard (2025), Status des Offshore-Windenergieausbaus in Deutschland. Retrieved on 26/11/2025 from https://www.wind-energie.de/fileadmin/redaktion/dokumente/publikationen-oeffentlich/themen/06-zahlen-und-fakten/20250204_Status_des_Offshore_Windenergieausbaus_Jahr_2024.pdf

- Eurostat (2025), Share of energy from renewable sources. Retrieved on 27/11/2025 from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/nrg_ind_ren/default/table?lang=en

- European Alternative Fuels Observatory (n.d.), Interactive Map. Retrieved on 12/12/2025 from https://alternative-fuels-observatory.ec.europa.eu/interactive-map

- Federal Government (n.d.), Die Nationale Wasserstoffstrategie. Retrieved on 18/09/2025 from https://www.bundeswirtschaftsministerium.de/Redaktion/DE/Wasserstoff/Dossiers/wasserstoffstrategie.html

- Federal Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Action (2020), The Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action presents a report on the plans for floating and fixed LNG terminals and their capacities. Retrieved on 18/09/2025 from https://www.bundeswirtschaftsministerium.de/Redaktion/EN/Pressemitteilungen/2023/03/20230303the-federal-ministry-for-economic-affairs-and-climate-action-presents-a-report-on-the-plans-for-floating-and-fixed-lng-terminals-and-their-capacities.html

- Federal Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Action (2020), Die Nationale Wasserstoffstrategie. Retrieved on 18/09/2025 from https://www.bundeswirtschaftsministerium.de/Redaktion/DE/Publikationen/Energie/die-nationale-wasserstoffstrategie.html

- Federal Ministry of Finance (2025), Bundeshaushalt: In die Zukunft investieren. Retrieved on 26/11/2025 from https://www.bundeshaushalt.de/DE/Schwerpunktthema/schwerpunktthema.html

- Federal Ministry of Justice (2025), Gesetz über den Bundesbedarfsplan (BBPlG). Retrieved on 20/11/2025 from https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/bbplg/index.html#BJNR254310013BJNE000803377

- Federal Network Agency (2025), Bundesnetzagentur approves hydrogen core network. Retrieved on 18/09/2025 from https://www.bundesnetzagentur.de/SharedDocs/Pressemitteilungen/EN/2024/20241022_H2.html

- Federal Network Agency (2024), Bundesnetzagentur confirms Electricity Network Development Plan 2023-2037/2045 for climate-neutral transmission network. Retrieved on 20/11/2025 from https://www.bundesnetzagentur.de/SharedDocs/Pressemitteilungen/EN/2024/20240301_NEP.html

- Federal Statistical Office (2025), Europa – Strompreise. Retrieved on 19/11/2025 from https://www.destatis.de/Europa/DE/Thema/GreenDeal/_Grafik/strompreise.html

- Fraunhofer ISE (2025), German Net Power Generation in 2024: Electricity Mix Cleaner than Ever. Retrieved on 18/09/2025 from https://www.ise.fraunhofer.de/en/press-media/press-releases/2025/public-electricity-generation-2024-renewable-energies-cover-more-than-60-percent-of-german-electricity-consumption-for-the-first-time.html

- German Trade & Invest (2020), German EV Charging Infrastructure Growing Dramatically. Retrieved on 18/09/2025 from https://www.gtai.de/en/invest/industries/mobility/automotive-industry/german-ev-charging-infrastructure-growing-dramatically-1804642

- Grid Development Plan Electricity (2023), Grid Development Plan Electricity 2037 with Outlook 2045, Version 2023, second draft. Retrieved on 19/11/2025 from https://www.netzentwicklungsplan.de/sites/default/files/2023-06/EN_GDP%20compact_2037_2045_V2023_2E_0.pdf

- Statista (2024), Renewable energy capacity globally by country. Retrieved on 26/11/2025 from https://www.statista.com/statistics/267233/renewable-energy-capacity-worldwide-by-country/?srsltid=AfmBOoqgTHjBpVT1h0b9wHdQDFmelmZm7mz1Sk2NMiENSpiXAoIjOwaF